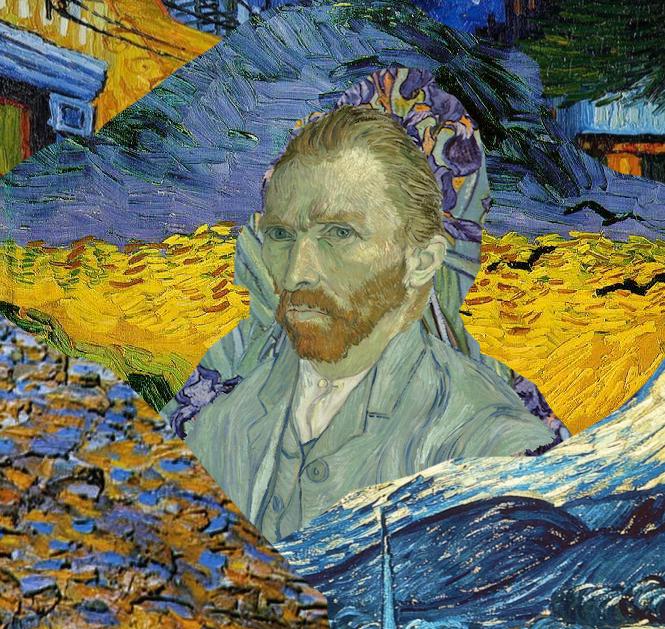

image created by Jenni Berrett.

I would take the deep depression, the irrational behavior, all of the real damaging parts of my disease, if I could just have the good stuff back...

The chairs in his office are straight-backed, hard, meant-to-look-leather vinyl. It’s not the psychiatrist's office of television; there is no leather chaise in a subtly-painted room, no studious man in low-lying spectacles, deliberately writing on a legal pad, nodding in affirmation. It’s just two hard chairs flanking a corner table that houses a lamp and a box of tissues. All of this next to his large wooden desk — scattered with coffee-stained journal studies — that faces a wall.

And a van Gogh.

Not an authentic van Gogh, of course. The furnishings here give this office away for what it is, and what it is, is an office that would never house a van Gogh. It’s The Starry Night print, naturally, probably ordered from a poster site online, framed in a black faux-wood frame, probably from Michaels, hung on this wall maybe just because it’s pleasing to the eye, or maybe because it subtly serves as a reminder that creativity is not limited by sanity. The original, painted June 1889, depicts the east-facing view from the window of the asylum into which van Gogh was voluntarily admitted. This one is east-facing too, as it were. I’ve seen The Starry Night in The Museum Of Modern Art, but even if I hadn’t, I’d know it. Everyone knows it.

Not everyone knows van Gogh was bipolar.

Not everyone knows I’m bipolar.

I didn’t always know I was bipolar.

My new psychiatrist wears a fuchsia linen shirt. He’s a tall, brilliant man with spiky black hair and shiny shoes, who hates mornings and says shit and fuck a lot. I like him. He replaced my first real psychiatrist: a man with a mild demeanor, three little girls, and a SunChips habit. I didn’t want a new psychiatrist — once you’ve divulged your darkest secrets to a stranger, watching them walk away is hard — but I got one, regardless.

So it was.

My first real psychiatrist was also the first professional I’d ever told about my spending into deep debt, clothing with tags attached filling my closet. The first one I told about my manic sexual behavior, my seemingly logical choices turned destructive, my all-night sewing/writing/organizing marathons, my sleep deprivation, suicidal ideations, erratic thoughts, and obsessions. He was the first to prescribe me ‘real’ meds — the ones that treated more than just my depression. He was the first person to treat my mania. He was the person that stole my mania.

I hated him. I loved him. I listened to him.

Dr. Matthew took my files from Dr. Hersevoort, and with them took me — my secrets, my fears, my illness.

On our first meeting I told him I was struggling to find words. This phenomenon, known as “word-finding”, is a psych med side effect you don’t hear about a lot. And it’s one you don’t think about a lot, until you need a word and your brain won’t find it and you look and look and after an eternity you just find a different word, one that says the same thing, but not the one you want.

It started for me in earnest when I started taking Lamotrigine. And it started hard. Overnight I went from immediate trouble-free information recall to nothing. Emptiness. I began asking friends and family to help me locate words. I became increasingly frustrated. I shed a lot of tears. I contemplated flushing my meds more than once.

I really wanted to.

I never did.

The thing about things like word-finding and exhaustion and sexual dysfunction and dry-mouth and nausea and the other things that come with the psych meds that save our lives is that they don’t seem like an issue — until they’re an issue. When I struggle for words people around me say things like, “Oh, welcome to being normal. You’re just like the rest of us now.”

When people say things about me being “normal,” I can’t hear them. All I hear is the voice whispering, Without the meds you’d be normal again. The thing that is abnormal for you is normal for me. I don’t care about normal as it’s defined by those around me. Because I don’t know that “normal.” I only know me, and the me I knew isn’t in there anymore.

When I sat with him for the first time — firm chair pressed into my tailbone, van Gogh staring me down from across the room — I told him I was going to quit taking meds. I was just done. I wanted my energy, my creativity, my words. My mania. I would take the deep depression, the irrational behavior, all of the real damaging parts of my disease, if I could just have the good stuff back — never mind that the good stuff eventually becomes the bad stuff; the energy giving way to the wreckage left in my wake.

He told me no. Instead of sending me out of his office with a pat on the back and a fond farewell, he pulled up a research study suggesting — proving even — that long-term SSRI use impacts sexual function, weight management, energy, and word-finding. He changed my meds: Added new ones, reduced existing dosages, changed others, and removed one. He told me to come back in six weeks.

And so I followed the regimen he gave me and made my follow-up appointment.

Which brings me back to the van Gogh and the fuchsia shirt and the spiky hair and the “I fucking hate mornings” exclamation, and the corner table with the tissues. And my tears.

This appointment was like all of the appointments, but also it wasn’t. This was the appointment where I could say that I feel some of the words returning. Only a few, here and there, but words, nonetheless. I could say that the changes he made, and continues to make, are giving me some of myself back. I could acknowledge that some of what I’ve lost may never return, and maybe someday I’ll forget it existed. But for now, I’ll take this, a tiny piece of the me I gave up.

I didn’t expect to end my appointment with mascara-stained cheeks. I didn’t expect there to be a cascade of emotions. I didn’t expect to see that van Gogh, the one I’ve seen so many times, and feel so profoundly what bipolar disorder has given to me, and what it has taken away.

I didn’t expect that a carefully-crafted blend of four medications would change my life so profoundly, turning the great peaks and valleys into foothills. I didn’t expect that I’d miss those peaks. I didn’t expect that I’d ever be able to see my illness as destructive. I didn’t expect that medication compliance would be the hardest and best thing I’ve ever done. And I didn’t expect that his tweaking could help me start to find words again. I didn’t expect that I’d thank the man I might have hated for changing everything for me.

Oh how I miss my mania; I expect that longing will never abate. But how grateful I am for science, and for the people who work to implement it — for Dr. Matthew and his insistence, and for van Gogh and his east-facing view.